Imagine yourself in the year 1870 somewhere in Michigan. You read in a local newspaper that five years ago, an Italian museum collector discovered a new rare cat in the high Andes of Bolivia. The collector claimed the total population was likely less than 3,000 individuals and, in the previous five years, a second individual had not been seen.

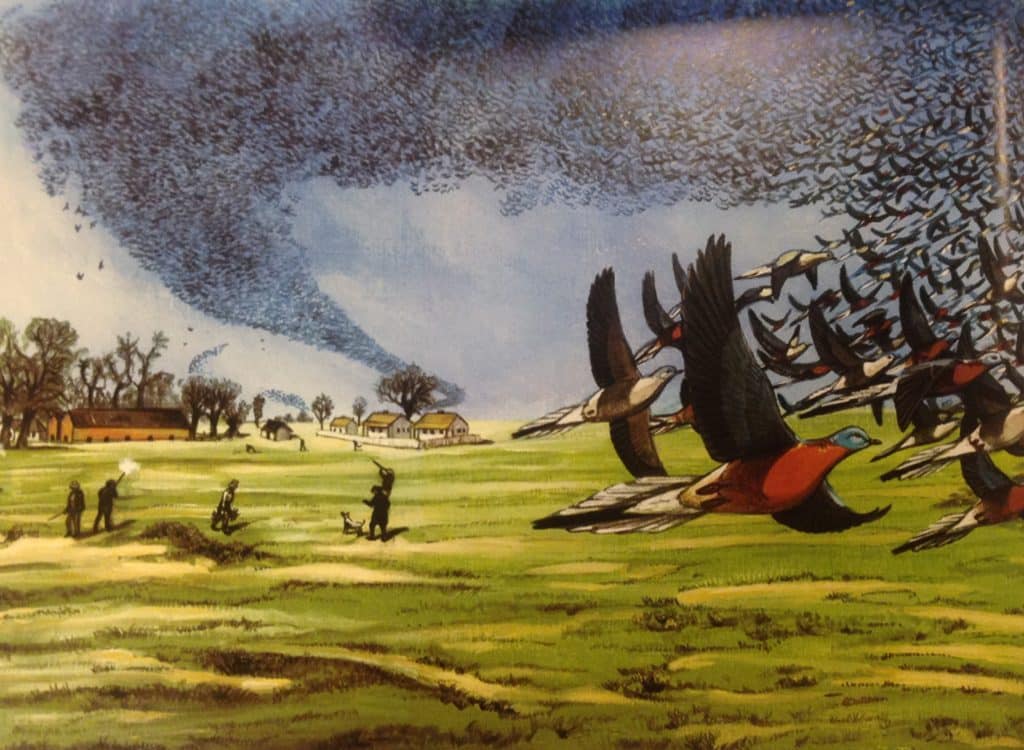

As you are enjoying your coffee, the sunlight dims. You hear a rushing sound but feel no breeze. Not high overhead, passenger pigeons—tens of millions of individuals, hour after hour, with no break between the endless stream of birds—are migrating in search of mast in beech forests. The flock stretches from horizon to horizon, their astonishing numbers uncountable. But you’ve observed this migration before and are grateful for the umbrella over your table.

Your erudite companion asks you, almost in jest, a simple question: Which do you suppose will go extinct first, the rare Andean cat or the ubiquitous passenger pigeon? Reasoning that since the cat’s population is less than one one-millionth of the pigeon’s population, the cat would most surely disappear first. You quip that the pigeon, whose droppings splat audibly on the umbrella, would likely never vanish.

But as this short story demonstrates, it’s not the size of the population that counts—it’s the threats that determine which species survive and which go extinct. Not unexpectedly, most people believe that rare species face a greater extinction risk than abundant species. Therefore, a particularly rare species would be far more likely to go extinct than a hyper-abundant species. But is such belief well-founded? The answer is no. In the absence of an understanding of threats, this belief is just that—nothing more than belief. But belief dies hard.

Today, with a total population estimated to be no more than 3,000 individuals and unlikely to have changed since its discovery, the Andean cat (Leopardus jacobita) remains equally rare and its habitat particularly inhospitable to humans. In stark contrast, from an estimated population of three to five billion individuals and once accounting for an estimated 24-40% percent of all land birds in North America, the last known individual passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) died in 1914. During the nesting season, every possible means was used to kill as many pigeons as possible to satisfy insatiable food market demand from Chicago to Boston. Humans reduced the largest known population of any species to zero. The passenger pigeon was officially extinct.

In the face of unmitigated, continuous, and unrelenting threats, some enabled by modern technological advances and free-market demands, no species on earth, however numerous, can now escape the possibility of being driven to extinction. Even species that are common today cannot be assured of being common in a year. Moreover, threats such as diseases can be invisible destroyers of populations. Spread by early Europeans in North America, smallpox decimated many Native American tribes even before direct conflict extracted its horrendous toll.

Some threats are unintentional yet can be equally devastating. The cancerous spread of palm oil plantations has made the tiny flat-headed cat (Prionailurus planiceps) the most threatened cat in the world.

Constant vigilance in the form of monitoring is a vital tool to avoid surprises. Therefore, all species, regardless of their numbers, require monitoring to make sure their status remains unchanged. Monitoring also serves as an early warning that threats have reared unexpectedly. I need not remind wild cat aficionados that all 33 species of small wild cats, without exception, require constant monitoring. Sadly, we are not there yet, but the Small Wild Cat Conservation Foundation and its global partners are doing everything we can to get us closer.