There’s no silver bullet to conservation. What works in one location may not work in another; or it may lose its efficacy over time as the pressures on that area shift. What works for one species will undoubtedly impact other species in that area. As John Muir once said, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe” – and we see that clearly when we look at the connection among elephants, bees, and honey badgers.

Elephants are notorious crop raiders, especially in areas where farmland overlaps with their habitat and historic migration routes. Save the Elephants’ Human-Elephant Co-Existence program, based just outside of Tsavo East National Park and led by Dr. Lucy King, aims to address this by working with local farmers to employ effective mitigation methods to protect their crops from elephants. Their flagship method is the beehive fence, the design of which is based on over a decade of research on elephants’ instinctive fear of honey bees – just like humans, elephants don’t like getting stung and will move away from active hives to avoid bees.

A beehive fence in action – an occupied hive deters this elephant from moving past the fence. Photo courtesy of Save the Elephants’ Elephants and Bees Project.

Elephants can destroy a farmers’ entire livelihood in a matter of minutes, eating and trampling crops, but a beehive fence can help deter crop-raiding by up to 80%. The fences are installed around subsistence farmers’ 1-2-acre plots of land, with between 12 and 16 hives hung from posts and connected to each other by wire. If an elephant runs into the wire, the nearby hives are disturbed and the bees aggressively come out to defend their hive – generally resulting in the elephants moving quickly away. It’s not 100% effective – no method is – but combined with other deterrent methods, it can mean the difference between a farmer having crops left to harvest and earn an income at the end of the year versus having nothing. The bees have some added bonuses for the farmers as well – they help pollinate crops and their honey can be sold, meaning additional income for the farmers.

But what the hives produce is appealing to other creatures as well – such as the infamous honey badger. Despite its name, the honey badger actually doesn’t consume a lot of honey, but rather goes after the brood (i.e. the developing bee larvae). Their coarse hair, loose fitting skin, and subcutaneous fat layer is thought to make them highly impervious to bee stings. Raids by honey badgers often damage the hive and cause the bees to abscond (i.e. abandon their hive). An unoccupied hive means the beehive fence is less effective at deterring elephants. So now a new question arises – how can the design of the fence be improved so that both elephants and honey badgers are effectively deterred?

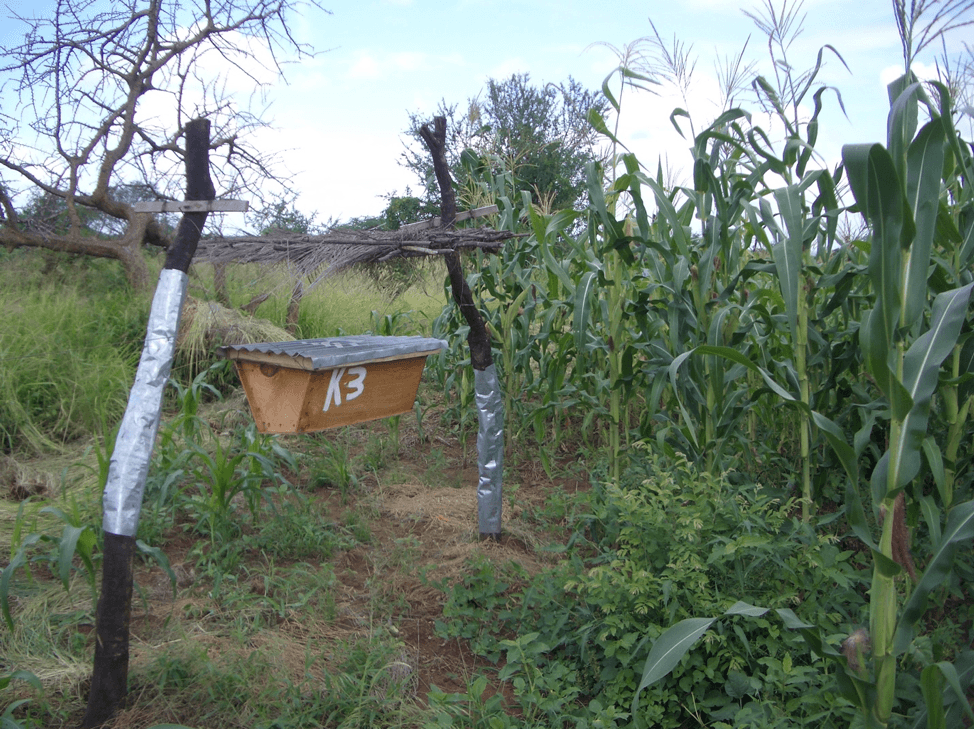

Abigail Johnson set out to answer this question. As a master’s student doing her field work with the Elephants & Bees Project, she worked with the local farmers to identify and test novel honey badger deterrent methods – including a motion-activated light, a cone baffle, and a cage-style deterrent placed over the hive that had recently been invented in the community by one highly innovative beehive fence farmer, Hesron Nzumu. Previously, the farmers had solely used iron sheeting wrapped around trees, which functioned to deter honey badger attacks by inhibiting their ability to climb the tree to access the hive. This method was better than nothing, but was still minimally successful at reducing absconding after an attack. The farmers needed more effective options and data to prove which one worked best.

Fence posts wrapped in iron-sheeting – a deterrent method that is better than nothing, but one that honey badgers can often overcome. Image © 2010 Lucy King

Fence posts wrapped in iron-sheeting – a deterrent method that is better than nothing, but one that honey badgers can often overcome. Image © 2010 Lucy King

Abi’s study looked not only at the effectiveness of three new deterrent methods but also the economic feasibility of each method in the study area. Camera traps captured honey badger activity and behavior at the test hives and also recorded the duration of the visitation (i.e. the number of minutes between the start of the attack and when the honey badger left the hive).

Motion-activated light deterrent method – honey badger can be seen in the grass below. This method was quite effective, but it is cost prohibitive in the community and the lights are prone to getting stolen. © 2018 Abi Johnson

Motion-activated light deterrent method – honey badger can be seen in the grass below. This method was quite effective, but it is cost prohibitive in the community and the lights are prone to getting stolen. © 2018 Abi Johnson

The success of the deterrents was measured by the honey badgers’ ability to access the hive, the severity of the attack, and whether the bees absconded as a result of the attack. Overall, the results showed that the three novel methods (motion-activated light, a cone baffle, and Nzumu’s cage deterrent) were a) each similarly effective, provided that they were installed properly, and b) all significantly more successful that the iron sheeting method – the novel deterrents collectively resulted in only 11% of hives absconding after an attack, versus 77% absconding when only the iron sheeting method was used. With fewer successful honey badger attacks, the beehive fences remain effective at deterring elephants and also maintain their stores of honey, which the farmers can harvest and sell for added income. Because of an extensive drought and lower hive occupation than normal, the sample size for this study was relatively small – but the results are promising and give the farmers a way to move forward with more effective honey badger deterrent methods.

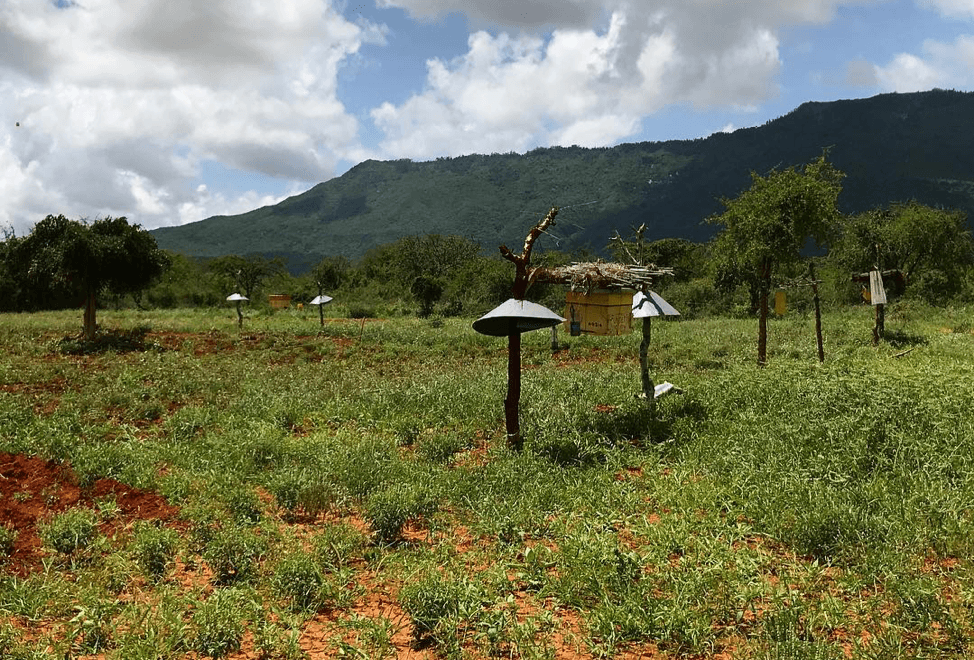

Cone-style deterrents set up around this beehive fence. These are an effective deterrent, but they require skilled labor to install. © 2018 Abi Johnson

Cone-style deterrents set up around this beehive fence. These are an effective deterrent, but they require skilled labor to install. © 2018 Abi Johnson

On the other hand, despite the relatively similar success of the three methods, economic feasibility plays into what method is most suitable for a given community. The light deterrents, while just as effective as the other methods, are both cost prohibitive and prone to getting stolen (25% of the units were stolen during the study). The cone deterrents were also relatively more expensive than the cage deterrents, combined with the fact that they required skilled labor to install. In the end, the study determined that Nzumu’s cage deterrent was most appropriate and viable for this area – it was the least expensive option and could be easily constructed by the farmers themselves.

With the option for farmers to better protect their hives from honey badger raids, each of the species tied into this project benefits – elephants are less likely to be persecuted by farmers when the hives remain occupied and the beehive fences are functioning effectively; bees are more likely to stay where they are and grow into stronger, healthier colonies; and honey badgers, whose population is on the decline, are less likely to be killed in retaliation by farmers whose hives have been raided. Though other factors will always come into play, this is a promising outcome for each of these species, and one that demonstrates the intricate connection among them all.

The Elephants and Bees team, wearing their beesuits, installing the cage deterrent designed by Nzumu on a beehive. The design makes it quite difficult for honey badgers to access the hive, but doesn’t hinder access for the bees. © 2018 Abi Johnson

Fence posts wrapped in iron-sheeting – a deterrent method that is better than nothing, but one that honey badgers can often overcome. Image © 2010 Lucy King

Fence posts wrapped in iron-sheeting – a deterrent method that is better than nothing, but one that honey badgers can often overcome. Image © 2010 Lucy King