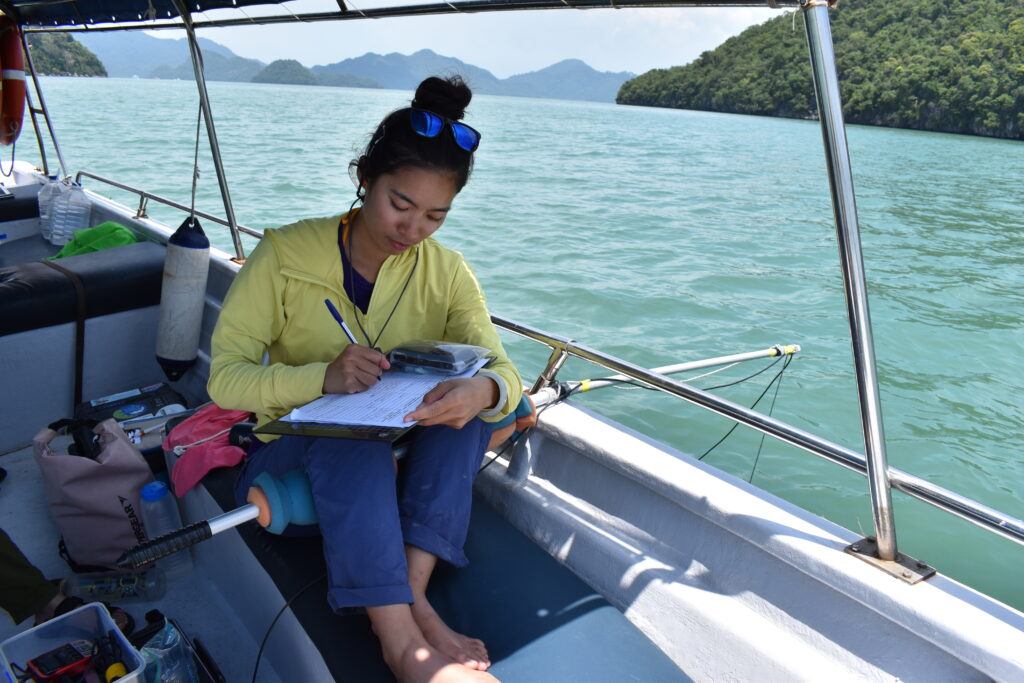

With the scream of a passing jet ski filling her ears, Dr. Saliza Bono watched the dolphins’ fins cut through the glittering waves 50 yards away. As the boat rocked with the current, she raised the pole and lowered the recording device into the water. She lives out her childhood dream as the Bioacoustics Officer for MareCet, studying the communication behavior of Malaysia’s marine mammals. Saliza, a WCN scholar and Rising Wildlife Leader, has led this innovative MareCet program since 2018, analyzing the underwater noises of cetaceans like this pod of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins swimming nearby. But beyond better understanding of dolphin communication, MareCet’s bioacoustics program has revealed something troubling—Malaysia’s oceans are getting louder, and it’s harming marine mammals.

Oceans are vast and often devoid of light, making visibility challenging. Marine mammals must rely on sound to communicate, navigate, and hunt throughout the deep blue. MareCet’s bioacoustics program helps shed light on how marine mammals function without depending on their vision. Saliza’s team tows hydrophones—underwater microphones—beneath their boat as they follow the dolphins. These hydrophones record all underwater sounds, meaning MareCet can pick up every dolphin click and whistle. The recordings are later analyzed by Saliza, who visualizes each sound on a spectrogram to determine the frequency levels used by dolphins.

Spectrograms also display the clamor of ship motors, propellers, and sonar. Tourist and fishing boat traffic is increasing throughout Malaysian waters, and sound from these vessels travels far across the ocean, even into marine protected areas, confusing and disrupting marine mammal behavior. Dolphins must communicate continuously to avoid being separated from each other and to detect nearby predators. When a container ship passes above two communicating dolphins, the noise—which is equivalent to a jet engine’s roar—drowns out their whistles. To compensate, the dolphins must increase their volume, similar to humans shouting at a loud concert. This is stressful for the dolphins, damages their larynxes and nasal sacs, and can lead to hearing loss. Noise pollution can even upset dolphin migratory patterns or cause mass strandings on beaches as they flee the painful, unbearable din.

MareCet’s spectrograms are key to identifying the negative impact of noise pollution on marine mammals. They share their bioacoustics data with the Malaysian government to influence policy to combat noise pollution, as currently few regulations exist. MareCet proposes reducing boat traffic, setting boat speed limits, and creating marine vehicle noise standards to help lessen the racket on and under the water. They also want noise pollution to be officially classified as marine pollution. Such legislation takes time to achieve, so MareCet also runs a mobile community outreach program to teach people about the threat of marine noise pollution.

As a fishing boat sputtered behind theirs, Saliza set her jaw and readjusted her grip on the hydrophone pole. MareCet’s bioacoustics research is crucial to marine mammal conservation, and next year they plan to expand the program to run 24 hours a day for several months. With luck, the data they gather will sway policymakers to protect dolphins and their habitats from the invasive drone of human activity.