If you’ve ever had the chance to see a yellow-naped parrot (Amazona auropalliata) up close, you wouldn’t be surprised to hear that they have captured the attention (and hearts!) of many. A few years ago, I traveled to El Jobo with Sam and Ted to see these birds in person for the first time. I didn’t know much about them at the time, having never seen one in person and honestly, knowing very little about parrots that didn’t live at our Punta Islita Breeding Center. Sam had heard that they could be seen flying to the islands in the area to roost, and we were discussing what time we were going to go looking for them, when we heard their signature “WAH-WAH” call right outside the window of our AirBnb! I was immediately fascinated by the uniqueness of their vocalizations, and they’re pretty adorable too.

Many people share my sentiment about the cuteness and uniqueness of these birds, which has unfortunately led to their decline, a trend too common among the parrots of the world. Yes, the pet trade strikes again. In fact, 90% of yellow-naped parrots nests are poached every year. With so few birds being added to the wild population, we can expect that they will continue to decrease in numbers unless we make some changes.

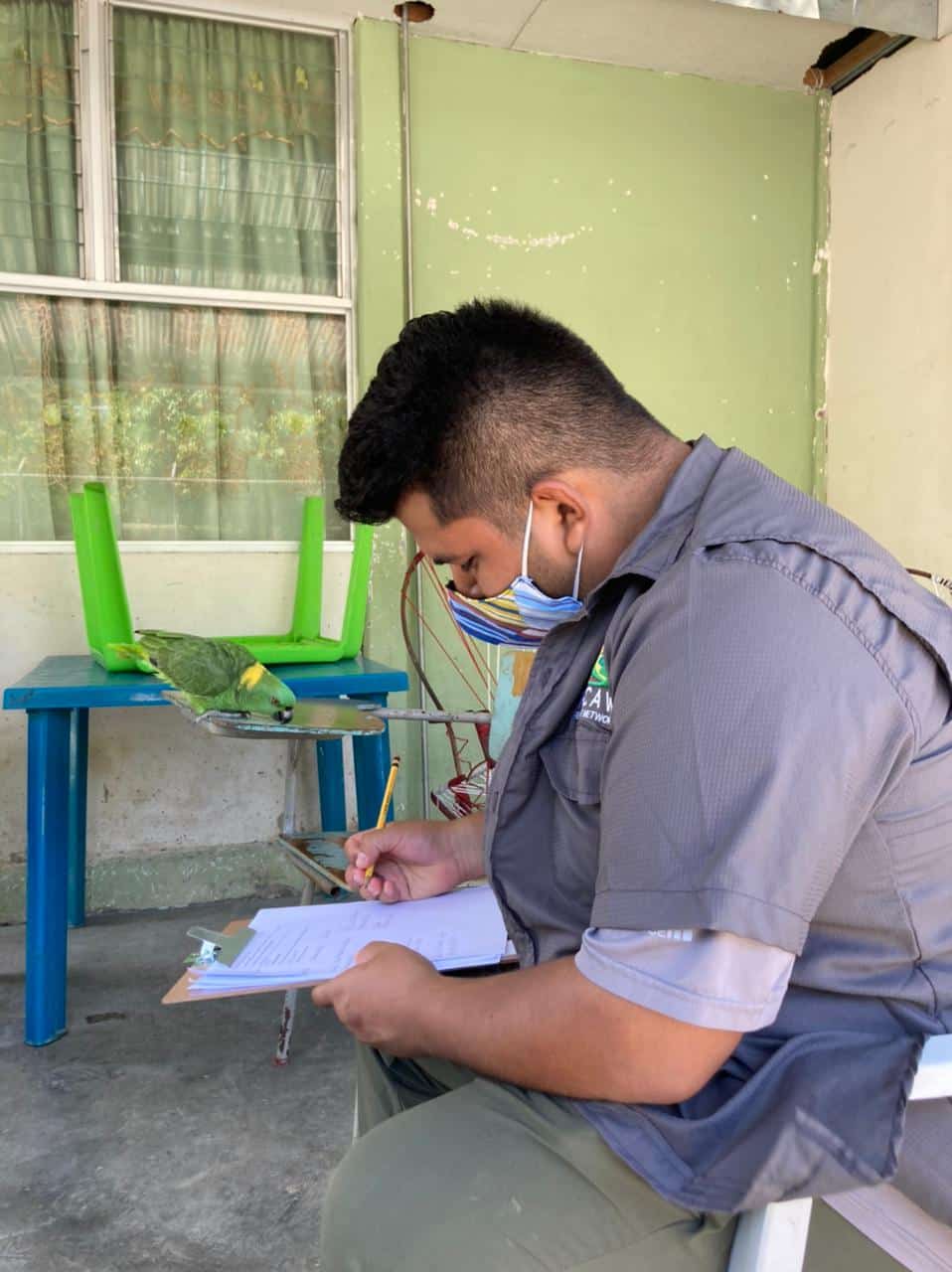

Poaching is a human activity, so it makes sense that to save this species, we must first look at the relationship between parrots and people within its range. Our Outreach Program Manager, Pamela Herrera Barquero enlisted the help of Brandon Zuñiga, and together they set off to better understand why so many parrot chicks were being stolen from their nests. As a life-long advocate for wild animals, when I hear the word “poaching,” I picture someone selfishly profiting off a defenseless animal, for no reason other than they are pure evil and hate animals. It’s easy to paint that picture, and to be angry at those who are keeping alive a demand for such an unsustainable market. But Pamela’s conversations with the locals in El Jobo paint a slightly different, or though still misguided, picture.

Yellow-naped parrots are kept as pets in many homes in Costa Rica, and it’s not because the locals don’t want to see the wild population doing well, but rather because they haven’t thought that far ahead. The adorable, wide-ranging vocalist has captured their hearts and they want it to be part of the family. It’s not an uncommon way for humans to look at animals, and it’s hard to fault them for it. After all, I grew up with a variety of pets, from snakes, to rabbits, to dogs, and I loved them all. The trouble is that there are simply not enough of these birds remaining in the wild. Keeping them as pets is a detriment to the species no matter how well they are loved. The Costa Rican government understands this, which is why there are laws that make it illegal to keep native species as pets. So, wait, why is this still occurring then?

Passing wildlife protection laws is great, but in order for them to be effective they need to be enforced. With 90% of yellow-naped parrot nests being poached, and Pamela and Brandon finding absolutely no shortage of them in homes during their study, we can clearly see that these laws are not being enforced. This led Pamela to her next study question: why aren’t police officers protecting these nests and confiscating illegally kept parrots?!

The answer, it turns out, is quite simple. They didn’t know. The truth is, this isn’t an uncommon phenomenon. It’s the trouble of communications from the top not getting to the bottom, and it happens all the time, all over the world. Law enforcement can’t protect if they don’t know who or what they are protecting, and they certainly can’t enforce what they don’t know they are supposed to enforce. Fortunately for the yellow-naped parrot, the police officers in El Jobo were willing to learn.

Pamela designed and hosted a police officer training workshop focused on the pet trade and the yellow-naped parrot. With the help of the Ministry of the Environment, the police officers learned the legal process of confiscations and how to conduct them safely. They then visited Las Pumas Rescue Center to see yellow-naped parrots up close so they could easily identify them in the future. By the end of the workshop, not only did the participating officers have a greater understanding of their role in protecting the parrots but were able to offer input about the resources they will need in order to successfully complete confiscations and protect nests in the future. While the workshop only had 15 participating police officers (so far!), the ripple effect of workshops like this can be magnificent. Those 15 police officers will go on to teach their colleagues what they have learned, and in doing so change the way police officers are trained when it comes to wildlife laws in the future. And with the help of our supporters, Macaw Recovery Network will make sure they are well equipped to do so. We’re all in this together.

There are a lot of lessons to be learned here, but I’ll focus on two: first, things are not always as they seem. And second, for the most part, people are willing to help when you give them the chance. If Pamela and Brandon had entered those communities with the mindset that keeping a parrot is evil, they wouldn’t have been as willing to listen to what locals had to say. As a result, they wouldn’t have seen that there is an abundance of hope for these parrots, since there is already an emotional connection between them and the local community. If Pamela had approached the police officers in an accusatory manner, placing blame on them for not doing a better job, she wouldn’t have seen that they are willing to help! They just didn’t know how.

It’s projects like these that remind us that without support from communities, what we do as conservationists has a very limited impact. With the help of the community, lasting change is possible. So in honor of these incredible birds that we all love so much, I will choose to be more open-minded about the people around me, and remember that together we can all thrive!