Fossilized riverbeds in Botswana. An Andean cat geoglyph in Chile’s Atacama Desert. A pre-Incan burial site in a remote region of Peru.

These archaeological treasures were recently discovered through the fieldwork of several conservation groups: Cheetah Conservation Botswana, Spectacled Bear Conservation, and Seeking the Andean Cat, a partner of Small Wild Cat Conservation Foundation.

Conservation benefits people and wildlife in many ways—some quite surprising. Besides connecting people to nature, providing alternative livelihood opportunities, and promoting traditional knowledge, wildlife conservation sometimes also helps reveal and protect historically significant sites.

In Chile’s Atacama Desert, the largest known geoglyph of a cat—over 200 feet long—was discovered last year thanks to footage from a drone survey by Seeking the Andean Cat. Together with Small Wild Cat Conservation Foundation (SWCCF), they conducted research about the meaning of this ancient artwork, which roughly dates back to 500 BC. With its distinctive body shape, spotted flank, and long, wide-ringed tail, the conservationists concluded that this geoglyph depicts the Andean cat, a species found in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. Lines radiating out from the geoglyph’s front likely represent the Andean Cat’s sacred role in Andean culture as an intermediary between heaven and earth through rain and water.

“This geoglyph represents the real belief and sacredness of the Andean cat for Andean culture,” said Rodrigo Villalobos of Seeking the Andean Cat, who made the discovery with SWCCF’s support. “These beliefs are still present in the remaining Quechua and Aymara people. We are running five local projects of citizen science and awareness to protect the species locally.”

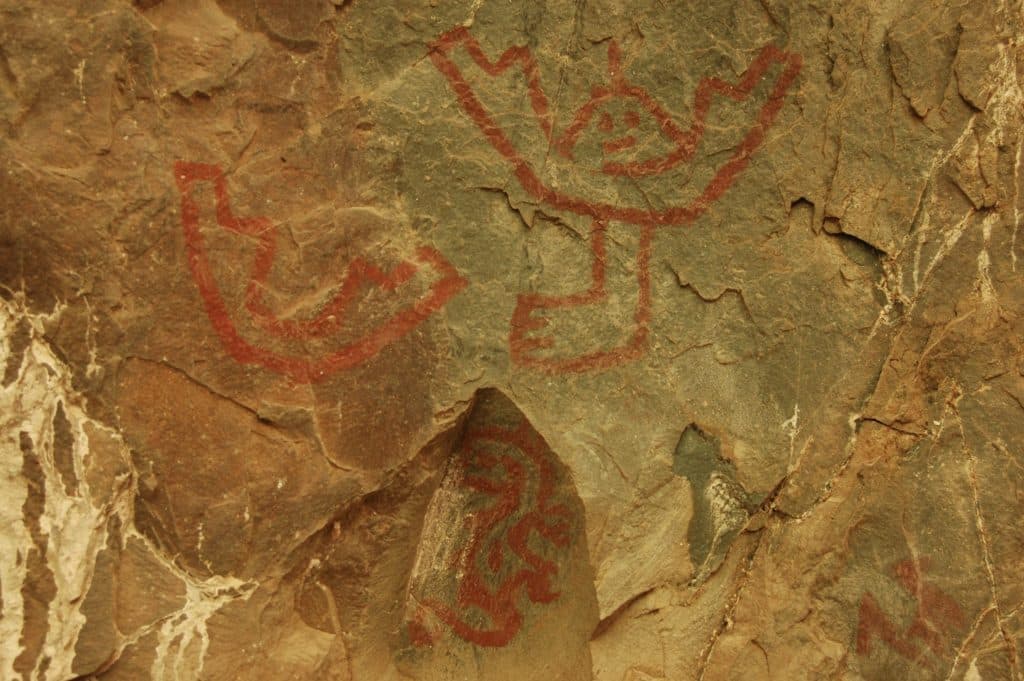

In northern Peru, Spectacled Bear Conservation (SBC) helps conserve local culture by identifying archaeological sites that they sometimes come across in the Lambayeque region, where the pre-Incan Sican culture was based. These sites can be over 1,000 years old, and some estimates indicate that up to 90% of gold Peruvian artifacts in museums around the world originate from this area. Peruvian law forbids looting and destruction of archaeological sites, but this is challenging to enforce in these remote areas, which are often habitat for spectacled bears. SBC’s field research team regularly discovers petroglyphs and artifacts while searching for undocumented bear populations, sharing location data and photos with the Sican National Museum and Peru’s Ministry of Culture. This helps improve protections to preserve culturally significant areas and prevents looters from disturbing or damaging them.

In Africa, Cheetah Conservation Botswana (CCB) held an extensive natural and cultural resource review in the Western Kalahari wildlife corridor, an important cheetah habitat. This review led to a number of remarkable discoveries, including a fossilized riverbed, ancient artifacts such as pipes made of bones, rock walls and boulders that traditional hunters used to sharpen their spears and arrows for generations, and mineral licks used by animals for so long that they became caves. CCB also discovered the graves of two adventurers whose plane crashed in 1968. These finds prompted Botswana’s Department of National Museums and Monuments to designate this region of the Okwa River Valley as a site of significant cultural heritage deserving protection from future land development, agricultural, and pastoral use. This will not only protect valuable cultural sites, but make the area safer for cheetahs as well.

WCN is proud to support our Conservation Partners around the world, whose work protecting wildlife can also contribute to safeguarding important historical and cultural landmarks.