If you’re an animal lover, odds are you’ve seen footage of wildlife conservationists deep in the field with dart guns trying to tranquilize wild animals. It may seem like an easy, quick process, and it may even seem alarming, but this is an important and relatively safe part of working with wildlife. From time to time, conservationists must incapacitate an animal to carry out operations that would be harder or even impossible to do while they’re awake. This could be anything from helping injured animals or putting GPS collars on wildlife for tracking purposes.

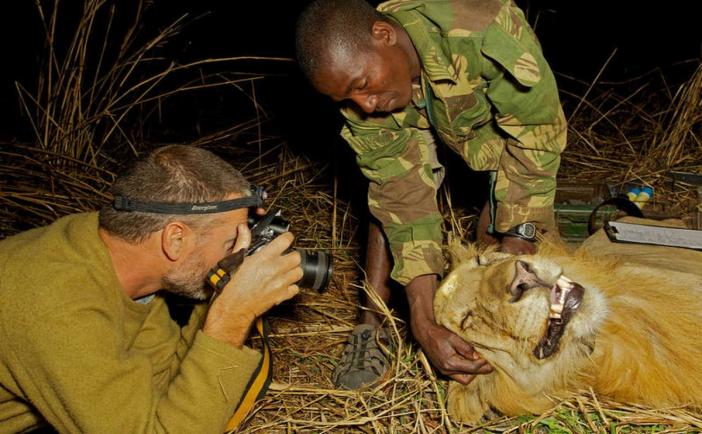

In Zimbabwe, for example, painted dogs often get caught in wire bushmeat snares which can dig into their skin causing lethal wounds; when Painted Dog Conservation discovers a dog with a snare wrapped around its neck they will dart the animal so they can safely remove it, clean the wound, and make sure the dog receives antibiotics. In Peru, Spectacled Bear Conservation were the first conservationists to put a GPS tracking collar onto a spectacled bear, this gave them extraordinary information on bear behavior and biology that is essential for bear conservation. Niassa Lion Project in Mozambique similarly tranquilizes lions to provide thorough physical inspections for health issues in places like the teeth or the paws that might not be visible to the naked eye. This kind of invaluable information is only possible to achieve by safely darting an animal so it can fall asleep for a limited amount of time. But just how complicated is this? It’s far more complicated than the quick knockout that we’ve all seen in cartoons or movies.

There are a wide variety of conditions to keep in mind to ensure the safety of both wildlife and the humans involved with the operation. Species, size, age, health, stomach contents (to make sure the animal doesn’t throw up and asphyxiate), and even the animal’s mood are just a few of the factors that can affect sedation. Hitting a mark with a dart can be notoriously inaccurate as it’s prone to losing its trajectory from minute environmental changes in temperature, humidity, and wind. Not only that, the feathered projectile moves slowly like a shuttlecock, quite often the animal can be out of the way before it even reaches the target. The dart itself is a ballistic syringe, which is fired with compressed gas from a non-lethal rifle and activated by the momentum of a steel ball in the syringe that pushes the plunger down and injects the animal upon impact. The best spot to aim for that would cause the least amount of pain would be a strong, muscled area like the rump or the thigh. Even though it is a non-lethal projectile, it would be painful to hit a sensitive part of the body. The effects are never instantaneous and may take up to an hour for the drugs to kick in. Before that, the animals can become more agitated and even hostile but you would be too if you were just minding your own business and got hit with a dart. The conservationists stay on guard to protect themselves but will still follow the animal closely to make sure that it doesn’t wander away and land in an unsafe location such as a pool of water or try to climb up a tree where it might lose its balance and hurt itself.

After the animal is asleep, conservationists will continue to monitor its vital signs, making sure it doesn’t overheat and can get enough oxygen. Conservationists make great efforts to ensure the safety of animals they dart, and again, they only tranquilize wildlife when it’s absolutely necessary to do so.

A lion in Mozambique is given a thorough examination and photographs are taken while he's down for the count to help them identify his face more easily in the future.

Darting is a risky process, one that requires conservationists to be stealthy, patient, and alert for the entire duration of the operation. But our conservationist partners and their teams are professionals who take the job seriously and do their best to make the process as smooth and seamless as possible. Conservationists use their expert knowledge and skill for the good of the individual animal and for the protection of the species as a whole. They’re able to do hands on examinations that can keep the animal as a healthy part of the ecosystem and they can use radio collars to monitor how wildlife is using the habitat they live in. After a successful operation, the animal will wake up about an hour later, a little groggy and confused but otherwise unharmed. They’ll wander back to the wilderness and return to their daily routine, a little better than they were before thanks to people who care about them.