When I visited Chile in 1997 to begin my PhD program for the Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation (WEC), University of Florida (UF), I had two objectives: Guigna ecology and Guigna conservation. As most UF-WEC graduate students discover, if threats are not mitigated first, there would be no individual cats left to study. Doing conservation in the form of threat reductions first changed my research questions. Examples have power and my own experience during my PhD work gave me vital information that changed my career path.

Even if a small cat is entirely unknown, if we know individuals are killed for preying on loose chickens, we can act to prevent retaliatory killing. Conservation in the form of active threat reduction must come first. Without threat reduction actions, they would not be any Guignas left to study. What I learned has rippled throughout my career. To be useful, research must be derived from conservation actions and need-to-answer questions. Therefore, research rarely comes first.

All the research in the world will not save Guignas or any other wild cats. Immediate threat reduction actions are needed. This means that anyone, especially those without any university experience whatsoever, can be conservation practitioners. Perhaps those with no interest in research are better at implementing practical, pragmatic threat reduction interventions because they are not distracted by their own curiosity to invent research questions.

I also realized I would not live long enough to save all small wild cats. I could neither go it alone nor go with the flow inside some big conservation organization. A novel approach was needed. A like-minded dedicated team was needed. Though I much prefer to work alone, the stakes were so high that it was more important for me to be a good team player, become a leader, and remain as independent as possible.

To conserve all small wild cats, collective action was urgently needed. Collective actions lead to large-scale changes. Remember the old adage: good research motivates more research. For many small wild cats, there is not time enough to study every species ad infinitum. Practical, pragmatic action-based threat reduction, not more research, was needed for many species.

Real change has rarely, if ever, come from the top down. To make change, we must be well-grounded. Though we must think globally, we must know what is happening locally and to make change. Therefore, a clear mission statement was needed that included a statement about how the mission would be achieved.

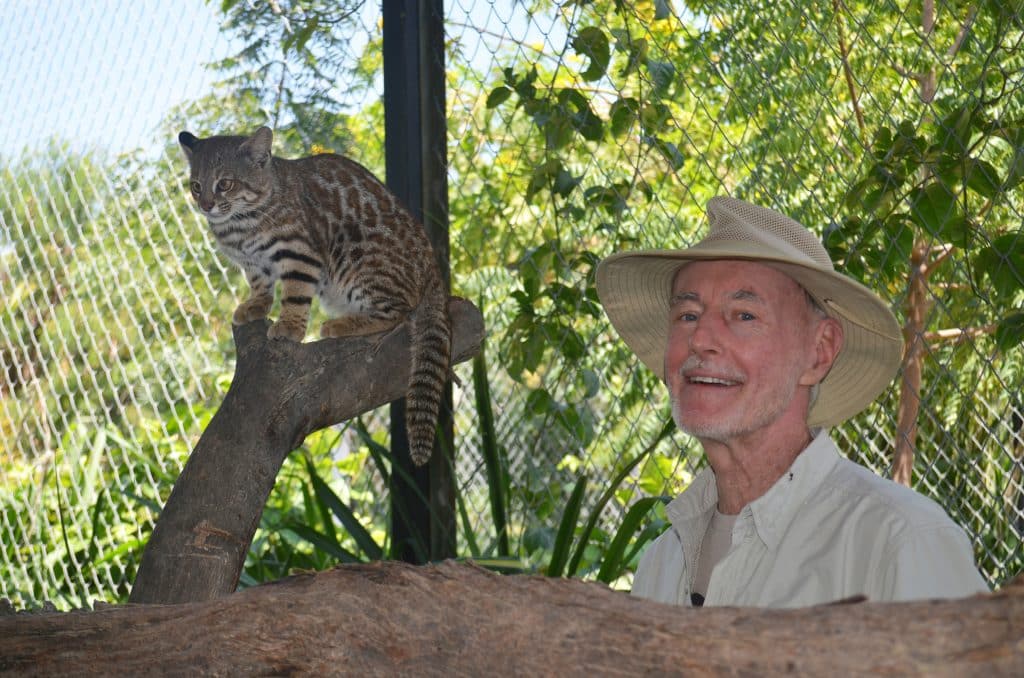

All the above is incorporated into Small Wild Cat Conservation Foundation’s (SWCCF) mission statement. SWCCF’s mission is to ensure the survival of small wild cats and their natural habitats worldwide. This mission is achieved by working with local partners around the world to identify and mitigate threats to the world’s small wild cats.

As a leader, I make an effort to be a good listener. To steer our efforts, I try to be clear about our objectives. I fully trust everyone I work with. It does not matter if a colleague has a PhD or no degree at all. If someone has a good idea, if someone has a better solution, I want to hear it. I make decisions on what people do, not their title or position. SWCCF is inclusive. Anyone anywhere can be a small cat conservation practitioner and a partner of SWCCF. There is no better time to become involved.

What qualities make a good small cat conservation practitioner? The four P’s: Passion, Patience, Perseverance, and Persistence. If you don’t have these qualities, you will most certainly learn them from the small wild cats.