On April 24, 2020, 12 rangers were tragically killed in Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, one of the most biodiverse protected areas in the world. Today on World Ranger Day, we take a moment to share their names, as initially reported by the Congolese Institute for the Conservation of Nature (ICCN), honor their lives lost too early, and reflect on the role of rangers in protecting wildlife:

- Abedi Iyalu Kadhafi, aged 23 years

- Anuari Bihira Lumumba, aged 27 years

- Badi Mukandama Djamali, aged 27 years

- Fazili Justin Junior, aged 29 years

- Kambale Mutsomani Jean-Louis, aged 31 years

- Kambale Teremuka Jules, aged 28 years

- Kasole Janvier Joseph, aged 30 years

- Mugisho Kulondwa Augustin, aged 27 years

- Muhindo Isevihango Jeannot, aged 30 years

- Muhindo Katembo Jacques, aged 29 years

- Ndagijimana Ndahobari Héritier, aged 27 years

- Paluku Kalondero Moise, aged 30 years

These rangers were not the intended targets of the killing, but lost their lives while responding to an attack on the local community, tragically leaving behind loved ones, brothers, sisters, friends, children, parents, and colleagues.

Unfortunately, this loss of life in Virunga National Park is not an isolated incident—more than 150 rangers in Virunga have been killed since 2006, a tragic situation all too familiar to wildlife guardians around the world. Despite these losses, conservationists and rangers continue to work for both economic and humanitarian development programs in partnership with and for the benefit of local communities, continuously striving for stability, justice, and peace.

Rangers, forest guards, warriors, scouts, field enforcement officers—the titles they serve under are many, but these brave women and men share a common purpose: protecting wildlife and wild landscapes around the world. Many of the animals they protect—like elephants, rhinos, and saiga antelopes—are among the most widely targeted by poachers and the illegal wildlife trade.

Recognition of the complexity of poaching and law enforcement is also vital to the alignment of wildlife conservation and social justice. Historically, poaching has been depicted as a one dimensional conservation problem. In fact, there are multiple facets to poaching, with innumerable categories and motives, including trophy, medicative, and consumptive poaching (Montgomery 2020). Recent studies show that many poachers are not always aware of the potential consequences of their actions on both their personal lives as well as their local ecosystems. The long-term goal of conservationists is not to exacerbate an endless conflict between poachers and rangers, but to improve the ability of humans and wildlife to coexist and thrive together. So in addition to law enforcement, rangers and conservationists also provide education and employment opportunities for communities to reduce threats to wildlife and dissuade poaching.

At WCN, we recognize the complex realities of law enforcement and wildlife protection. Conservation should never lead to the loss of human life. With this in mind, WCN supports a range of community-based conservation approaches that provide community members with livelihood opportunities that relieve pressure on wildlife. Our conservation Partners around the world demonstrate that wildlife protection can be achieved in a variety of ways, with eco guardians like rangers working in conjunction with community members.

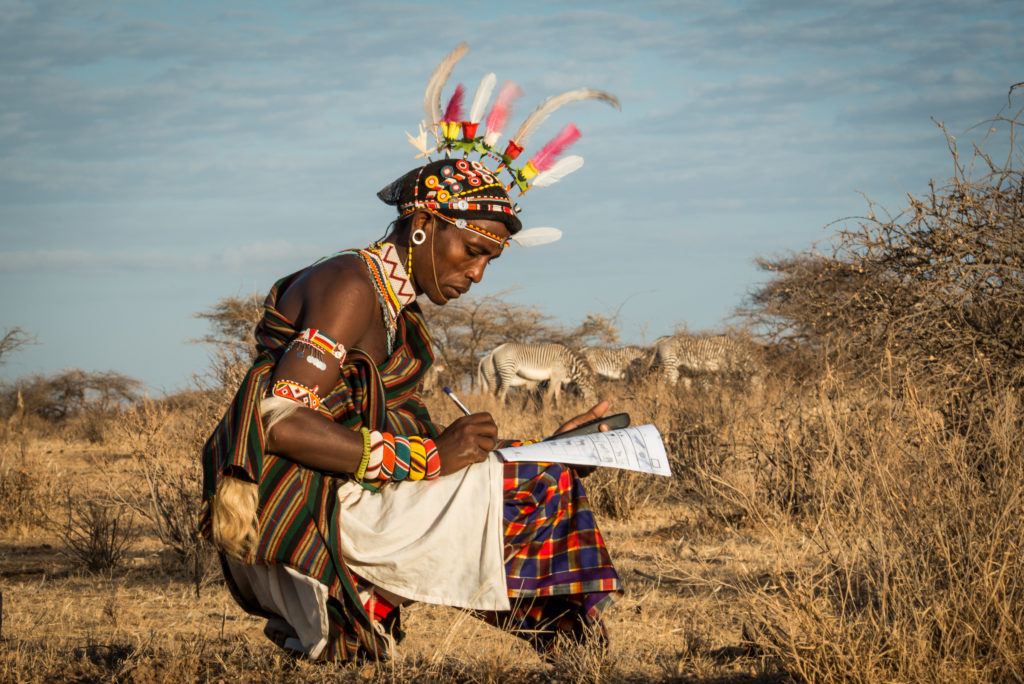

In northern Kenya, home to the beautiful Grevy’s zebra, local Samburu warriors are employed by the Grevy’s Zebra Trust (GZT) as Grevy’s Zebra Warriors. Through Ewaso Lions’ Warrior Watch program, Samburu warriors also act as lion ambassadors in their local communities. Both of these warrior groups play a critical role in monitoring wildlife populations, raising awareness about them in their respective communities, reducing human-wildlife conflict, and advocating for peaceful human-wildlife coexistence.

In Zimbabwe, Painted Dog Conservation’s Anti-Poaching Unit, composed of highly trained scouts who work closely with the Zimbabwe Parks & Wildlife Management Authority and Forestry Commission, patrol the areas bordering the Hwange National Park daily, searching for poachers and snares. Since 2001, the scouts have collected more than 30,000 snares—sparing nearly 3,000 animals from the traps—and they have managed to keep poaching within the area under reasonable control.

Across Russia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia, rangers supported by the Saiga Conservation Alliance (SCA) work in extreme weather conditions, often in frigid weather, to protect saiga antelope across their entire range. As another reminder of the threats these rangers face, Kanysh Nurtazinov, a ranger protecting saiga in Kazakhstan, was killed by poachers at the age of 43 in July 2019. One year after his death, the SCA team continues to honor Kanysh’s life. In this in-depth blog, a ranger from Russia’s Stepnoi Reserve provides a glimpse into what protecting this ancient species entails.

Conservationists are witnessing increased pressure on wildlife during the COVID-19 pandemic due to reduced conservation funding, movement restrictions placed on local teams, and the collapse of community-based ecotourism enterprises (Lindsey et al. 2020). As poverty among rural communities increases, people are being forced to depend more on their local natural resources for economic support, including wildlife. So the economic and social security of communities surrounding protected areas and wildlife during this period is of utmost importance, as less pressure on the community also means a safer space for both rangers and wildlife.

As an international conservation community, we must also honor both rangers and the communities they serve by understanding the complex history of international wildlife conservation’s links to colonization and militaristic tendencies. Conservation has a long history of removing native people from their land in the interest of preserving wildlife. It’s been a model that sees human occupation as incompatible with conservation, despite evidence that indigenous people can play a crucial role in protecting biodiversity. Even in extreme cases, military intervention can only be a short-term strategy; in the long term, what’s needed is support from the communities in and around wild landscapes. We recognize that it is now more important than ever for rangers, conservation NGOs, and local stakeholders to work together to resolve any threats in a proactive and peaceful manner.

As many of us adore wildlife from the safety of our homes, brave individuals around the world are risking their lives in the field everyday to protect these vulnerable species. By supporting the financial and social wellness of communities, especially during these times of global suffering, peaceful coexistence between humans and wildlife can be a reality. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, WCN has deployed emergency funding to support this critical work done by rangers. We hope that there will be a time soon when rangers can take a day off knowing that both local communities and the global conservation community have their back!

Thank you to all of the rangers, forest guards, warriors, scouts, and field enforcement officers around the world. We hope you, and the communities you support, all stay safe!